3 ways Sinophobia may go unchecked in your life

Posted by Hannah Bae

March 24, 2020

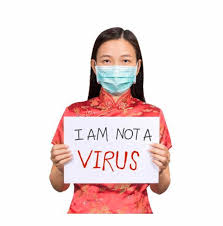

After news of the Coronavirus in Wuhan broke, I braced myself for the waves of Sinophobia (anti-Chinese sentiment), racism, and discrimination that would quickly target East Asians. It was only a matter of time before I came across an article from a U.S. outlet which labeled a (misattributed) video of a Chinese woman eating a bat as “disgusting,” claiming that the exotic animal trade in China made its people deserving of Coronavirus.

This angered me, but Sinophobia in America is hardly new. So, today I want to talk about three ways you may see it occur in your own life:

1. The Coronavirus travel ban (well, Coronavirus fear-mongering in general).

In 2009, when the H1N1 virus emerged as the most common cause of influenza and rapidly spread across the world, the World Health Organization (WHO) did not recommend a travel ban. In late January, a travel ban was already enacted to prevent the spread of Coronavirus, despite evidence stating that bans are not an effective technique.

Furthermore, this virus (commonly called the Swine Flu) was first detected in the United States. However, unlike the Coronavirus, Americans were not blamed for the spread of the virus.

Now, as the Coronavirus spreads, blame attributed to various cultural practices and behaviors- specifically those associated with Chinese people- has raced across the Internet. But the discrimination East Asians are facing isn’t simply online; recently, an East Asian woman was attacked for simply wearing a mask at an NYC subway station.

In Sydney, Australia: a Chinese man died from a potentially nonfatal heart attack because bystanders were reportedly too scared to assist with CPR out of fear of contracting Coronavirus.

Let’s think critically about why the reactions to these two viruses might differ so vastly.

2. Chinese Restaurant Syndrome

You may have seen this term floating around! There’s recently been some national spotlight on the phrase as a campaign (justifiably) argues for its redefinition.

Initially, the term was defined (by Merriam-Webster) as “A group of symptoms (such as numbness of the neck, arms, and back with headache, dizziness, and palpitations) that is held to affect susceptible persons eating food and especially Chinese food heavily seasoned with monosodium glutamate (MSG).”

This is problematic not only because of the harmful assumptions it makes about Chinese culture, but also because the connection between the listed symptoms and MSG has been largely debunked by scientific studies. While MSG— again, commonly associated with Chinese food— is unfairly faced with regulatory and political pressures, other additives and preservatives (such as sodium nitrite), are allowed to exist without scrutiny.

Now, why might that be?

3. U.S. government’s anti-Chinese rhetoric.

This example more explicitly relates to Sinophobia than the ones we’ve discussed previously, which– while valid– are arguably are a bit more insidious.

The language, sentiments, and actions that our government employs matter. Under Trump’s administration, we’ve seen a noticeable uptick in the inflammatory language being used against China (and by extension, Chinese people). While this uptick certainly doesn’t exist in a vacuum, it’s worth noting that the outright hostility we’re seeing throughout Chinese-American relations is entering some new and concerning heights.

When we see our government adopt an anti-China stance, nationalism can quickly encourage “patriotic” citizens to join in on bashing China and its citizens.

Sure, all governments (including the Chinese government!), can and should be subject to criticism. However, American citizens should think carefully about the narratives and propaganda fed to them before participating in such criticism.

How else do you see Sinophobia in your life? How can you help stop the spread of anti-Chinese sentiment?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.